What is valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)?

What is valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)? Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) is a disease caused by fungi (Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii species) that in about 50%-75% of normal (not immunocompromised) people causes either no symptoms or mild symptoms and those infected never seek medical care; when symptoms are more pronounced, they usually present as lung problems (cough, shortness of breath, sputum production, fever, and chest pains). The disease can progress to chronic or progressive lung disease and may even become disseminated to the skin, brain (meninges), skeleton, and other body areas. The disease can also infect many animal types (for example, dogs, cattle, otters, and monkeys).

Most microbiologists and infectious disease physicians prefer the name coccidioidomycosis because the word describes the disease as a specific fungal disease, and this term may replace valley fever in the future. This disease has several commonly used names (valley fever, San Joaquin Valley fever, California valley fever, acute valley fever, and desert fever). Other names get confused with valley fever (for example, rift or African valley fever, which is caused by a virus).

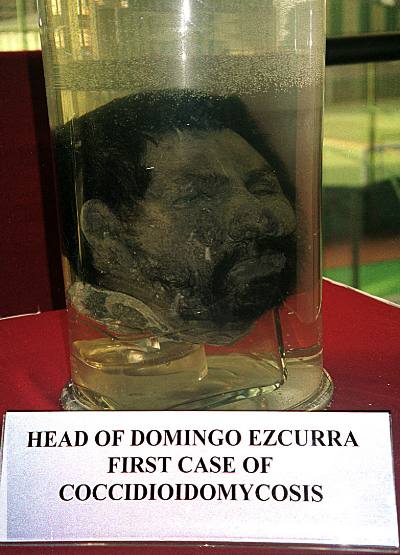

Coccidioidomycosis was first noted in the 1890s in Argentina; tissue biopsies of people with the disease showed pathogens that resembled coccidia (protozoa). During 1896-1900, investigators learned the disease was caused by a fungus, not protozoa, so the term "mycosis" was eventually added to "coccidia." The disease is often noted to occur in outbreaks, usually when soil is disturbed and dust arises, and when groups of people visit an endemic region (such as San Joaquin Valley or Bakersfield, California, and Tucson, Arizona, or parts of southern New Mexico or west Texas) during late summer and early fall. The disease is not transmitted person to person; it is acquired from the environment via contaminated soil and dust. About 100,000 cases are diagnosed each year in the U.S.

What causes valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)?

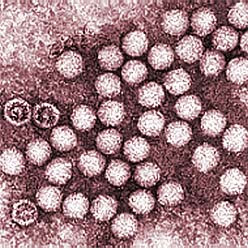

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by two species of fungi, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Both are dimorphic (having mycelial and spore phases), almost always acquired through the respiratory tract by inhalation. When viewed microscopically, the mycelial form found in the soil has arthroconidia (barrel-shaped asexual spores) attached to non-spore-forming rectangular mycelium cells, usually alternating in a line. Once the arthroconidia are inhaled, the fungus develops into 30-60 micron diameter spherules that are filled with 3-5 micron diameter endospores. The large spherules then release the endospores that continue the infection; microscopic identification of these endospores in pus or tissue confirms the diagnosis.

|

| Picture of Coccidioides immitis fungal organism |

Pictures of Coccidioides immitis and lung X-rays can be seen in the first and third Web sites listed below.

What are the symptoms of valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)?

About 60% of all infected people (without immunosuppression) have no symptoms and do not seek medical care. About 30%-35% of people who develop symptoms have flu-like symptoms (fever, cough, malaise, and chills) that resolve over about two to six weeks without treatment. Some may develop additional symptoms such as shortness of breath, night sweats, headaches, sputum production, and joint and muscle pains (symptoms resembling pneumonia). Women, more often than men, may develop erythema nodosum (reddish, painful, tender lumps, usually on the legs) or erythema multiforme (an allergic reaction similar to erythema nodosum in multiple body sites with rash). Usually these symptoms resolve in about two to six weeks.

Chronic coccidioidomycosis occurs in about 8% of patients and is characterized by the above symptoms but may spread from the lungs to other parts of the body. People develop lung cavities that may disappear in about two years or become calcified.

Progressive pulmonary coccidioidomycosis includes the above symptoms but progresses to lung volume loss, fibrosis (scarring), and inflammation.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis (about 1% of cases) can be characterized by the above symptoms, but they may occur over weeks to years. The fungi may be found in any body organ but are most frequently seen in the skin, meninges, and bones. In a few cases, the disease is rapidly fatal. Disseminated disease occurs most often in immunosuppressed individuals, males, and pregnant females.

How is valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) diagnosed?

Accurate diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis is important because there are many diseases that have similar initial symptoms and may occur in areas of the world where coccidioidomycosis occurs; for example, Andes virus (caused by a hantavirus), arbovirus encephalitis (caused by six different viruses), Argentine hemorrhagic fever (an arenavirus infection caused by Junin virus), cryptococcosis (caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungal species), and others. Fortunately, a confirmative diagnostic test is easily done by microscopic examination of sputum or a tissue biopsy that show characteristic fungal spherules and endospores of Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii. These fungi can also be identified after they are cultured on fungal media (growth takes about five days). Additionally, there are several serum tests and a PCR test (to detect the genetic material of the fungus) that are available. High blood levels of IgG (an immunoglobulin) that react with the fungi can help determine the extent of the disease. Skin tests can determine if the person has been exposed to the fungi, but the test is not very specific or sensitive.

Other tests help determine the extent of the disease. The most frequent test is a chest X-ray to identify abnormalities in the lungs. MRI and CT scans are used to examine brain or other organ (especially bone) involvement. Bone scans also help to determine the presence of bone involvement. Most physicians will do other routine blood tests such as a CBC (complete blood count) and ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a marker of inflammation) test.

Occasionally, the diagnosis may require obtaining samples of tissue or tissue fluid, so lumbar puncture, bronchoscopy, and surgical or needle biopsy may be done.

How is valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) treated?

The majority of cases (over 60%) spontaneously resolves and requires no treatment. However, there are several antifungal drugs available to treat coccidioidomycosis if needed. The drug of choice is usually amphotericin B, but oral azoles (fluconazole [Diflucan], itraconazole [Sporanox], ketoconazole [Nizoral]) and a triazole (posaconazole) can be used. A new drug called voriconazole may also be used. Most of these drugs have side effects, and most have not been proven safe to use in pregnant patients except for amphotericin B. High relapse rates can occur with some patients (about 75% relapse with brain involvement), requiring lifelong antifungal therapy. In general, dosage (especially pediatric), length of time of drug administration, and the choice of drug is best decided in consultation with an infectious disease specialist.

Surgical treatment is sometimes needed. Pulmonary cavities, persistent pulmonary infection, empyema (pus collection), and shunt placement are some of the surgical interventions used to treat this disease.

Other treatments (for example, prednisone [Deltasone, Liquid Pred] or alternative therapy such as dietary modification) are not currently recommended by most physicians; people should consult with their physician before trying to use such methods.

What is the prognosis (outcome) for valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)?

The majority of people who get infected with the Coccidioides fungi have a good prognosis, as the infection is usually self-limiting. Some people with self-limiting disease may get a few small calcified areas in the lung, but these often cause no problems for the person. Chronic disease may produce more nodules and cavities in the lung and take a year or two to resolve, but usually the prognosis is good for many patients.

However, people with diabetes or the elderly have a only a fair prognosis, as they can develop progressive pulmonary disease with symptoms (shortness of breath, lung fibrosis, and cavities in the lungs) that persist for years. Progressive coccidioidomycosis has a poor prognosis. About 1% of patients are at high risk (usually immunosuppressed due to HIV, cancer, or chemotherapy) for developing disseminated coccidioidomycosis, and these patients have a grave prognosis. Patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis can have rapid development of all the symptoms listed above and die if the disease is not appropriately and rapidly treated.

What are the risk factors for developing valley fever (coccidioidomycosis)?

People living in the endemic areas (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) have been estimated to have a 1 in 33 chance of acquiring the disease; that chance increases the longer they reside in the area. However, even people simply passing through the area can get the disease. Males and pregnant females have a higher risk of getting the disease. People who do construction or farm work, especially the type that disturbs the soil, and any immunosuppressed person has an increased risk of developing valley fever (coccidioidomycosis).

Can valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) be prevented?

Research is progressing at several laboratories, but to date there is no vaccine available to prevent coccidioidomycosis in humans. People who live in endemic areas (see map in the last Web citation) of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas are likely to be exposed to the organisms since they occur in soil and dust. People who are more susceptible to the disease (for example, immunosuppressed people such as those with HIV/AIDS or cancer, the elderly, and pregnant females) should avoid new construction sites and stay indoors on dusty days. Soil in these areas can be moistened to prevent dust formation, and some investigators suggest that susceptible people should wear dust masks if dust exposure is likely. People who get the disease usually develop immunity to it, and unless their immune system is compromised, will not get the disease again.

Where can one find more information on valley fever?

http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/mycology/mycology-6.htm

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/215978-overview

http://www.cdc.gov/nczved/dfbmd/disease_listing/coccidioidomycosis_gi.html#9

http://geopubs.wr.usgs.gov/open-file/of00-348/of00-348.pdf

Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) At A Glance

- Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) is a disease caused by a fungus, Coccidioides, which lives in the soil of relatively arid regions (southwest U.S.).

- People are infected by inhaling dust contaminated with Coccidioides; the fungus in not transmitted person to person.

- Although most people infected with Coccidioides have no symptoms, if symptoms develop, they usually occur in the lung and initially resemble the flu or pneumonia (cough, fever, malaise, sputum production, and shortness of breath).

- Some people are more susceptible to infection (immunosuppressed people, those with HIV or cancer, and pregnant females) and may develop widespread disease.

- Diagnosis is usually easy to accomplish, and the disease can be treated by several antifungal medications; there is no vaccine available for valley fever (coccidioidomycosis).

Source

|

Bookmark this post:

|

|

0 comments

Post a Comment