What is ascites?

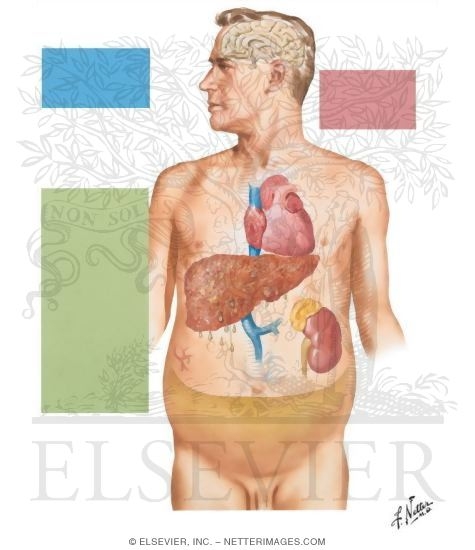

Ascites is the accumulation of fluid (usually serous fluid which is a pale yellow and clear fluid) in the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity. The abdominal cavity is located below the chest cavity, separated from it by the diaphragm. Ascitic fluid can have many sources such as liver disease, cancers, congestive heart failure, or kidney failure.

What causes ascites?

The most common cause of ascites is advanced liver disease or cirrhosis. Approximately 80% of the ascites cases are thought to be due to cirrhosis. Although the exact mechanism of ascites development is not completely understood, most theories suggest portal hypertension (increased pressure in the liver blood flow) as the main contributor. The basic principle is similar to the formation of edema elsewhere in the body due to an imbalance of pressure between inside the circulation (high pressure system) and outside, in this case, the abdominal cavity (low pressure space). The increase in portal blood pressure and decrease in albumin (a protein that is carried in the blood) may be responsible in forming the pressure gradient and resulting in abdominal ascites.

Other factors that may contribute to ascites are salt and water retention. The circulating blood volume may be perceived low by the sensors in the kidneys as the formation of ascites may deplete some volume from the blood. This signals the kidneys to reabsorb more salt and water to compensate for the volume loss.

Some other causes of ascites related to increased pressure gradient are congestive heart failure and advanced kidney failure due to generalized retention of fluid in the body.

In rare cases, increased pressure in the portal system can be caused by internal or external obstruction of the portal vessel, resulting in portal hypertension without cirrhosis. Examples of this can be a mass (or tumor) pressing on the portal vessels from inside the abdominal cavity or blood clot formation in the portal vessel obstructing the normal flow and increasing the pressure in the vessel (for example, the Budd-Chiari syndrome).

There is also ascites formation as a result of cancers, called malignant ascites. These types of ascites are typically manifestations of advanced cancers of the organs in the abdominal cavity, such as, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, lung cancer, or ovarian cancer.

Pancreatic ascites can be seen in people with chronic (long standing) pancreatitis or inflammation of pancreas. The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis is prolonged alcohol abuse. Pancreatic ascites can also be caused by acute pancreatitis as well as trauma to the pancreas.

What are the types of ascites?

Traditionally, ascites is divided into 2 types; transudative or exudative. This classification is based on the amount of protein found in the fluid.

A more useful system has been developed based on the amount of albumin in the ascitic fluid compared to the serum albumin (albumin measured in the blood). This is called the Serum Ascites Albumin Gradient or SAAG.

- Ascites related to portal hypertension (cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, Budd-Chiari) is generally greater than 1.1.

- Ascites caused by other reasons (malignant, pancreatitis) is lower than 1.1.

What are the risk factors for ascites?

The most common cause of ascites is cirrhosis of the liver. Many of the risk factors for developing ascites and cirrhosis are similar. The most common risk factors include hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and long standing alcohol abuse. Other potential risk factors are related to the other underlying conditions, such as congestive heart failure, malignancy, and kidney disease.

What are the symptoms of ascites?

There may be no symptoms associated with ascites especially if it is mild (usually less than about 100 – 400 ml in adults). As more fluid accumulates, increased abdominal girth and size are commonly seen. Abdominal pain, discomfort, and bloating are also frequently seen as ascites becomes larger. Shortness of breath can also happen with large ascites due to increased pressure on the diaphragm and the migration of the fluid across the diaphragm causing pleural effusions (fluid around the lungs). A cosmetically disfiguring large belly, due to ascites, is also a common concern of some patients.

When should I call my doctor about ascites?

People with ascites should be routinely followed by their primary physician and any specialists that may be involved in their care. Gastroenterologists (specialists in gastrointestinal diseases) and hepatologist (liver specialists) commonly see patients with ascites due to liver disease. Other specialists can also care for patients with ascites based on the possible cause and the underlying condition. The specialists usually ask the patient to first contact their primary physician if ascites increase. If ascites is causing symptoms of shortness of breath, abdominal discomfort ,or inability to do normal daily tasks such as walking, the patient's primary doctor should be notified.

How is ascites diagnosed?

The diagnosis of ascites is based on physical examination in conjunction with a detailed medical history to ascertain the possible underlying causes since ascites is often considered a nonspecific symptom for other diseases. If ascites fluid is greater than 500ml, it can be demonstrated on physical examination by bulging flanks and fluid waves performed by the doctor examining the abdomen. Smaller amounts of fluid may be detected by an ultrasound of the abdomen. Occasionally, ascites is found incidentally by an ultrasound or a CT scan done for evaluating other conditions.

Diagnosis of underlying condition(s) causing ascites is the most important part of understanding the reason(s) for a person to develop ascites. The medical history may provide clues to the underlying cause(s) and typically includes questions about previous diagnosis of liver disease, viral hepatitis infection and its risk factors, alcohol abuse, family history of liver disease, heart failure, cancer history, and medication history.

Blood work can play an essential role in evaluating the cause of ascites. A complete metabolic panel can detect patterns of liver injury, functional status of the liver and kidney, and electrolyte levels. A complete blood count is also useful by providing clues to underlying conditions. Coagulation (clotting) panel abnormalities (prothrombin time) may be abnormal because of liver dysfunction and inadequate production of clotting proteins.

Sometimes the possible underlying causes of ascites may not be determined based on the history, examination, and review of laboratory data and imaging studies. Analysis of the fluid may be necessary in order to obtain further diagnostic data. This procedure is called paracentesis, and it is performed by trained physicians. It involves sterilizing an area on the abdomen and, with the guidance of ultrasound, inserting a needle into the abdominal cavity and withdrawing fluid for further analysis.

For diagnostic purposes, a small amount (20cc, for example) may be enough for adequate testing. Larger amounts can be withdrawn if needed to reveal symptoms associated with increased abdominal ascites, up to a few liters (large volume paracentesis).

The analysis is done by sending the collected fluid to the laboratory promptly after drainage. Typically, the number and components of white blood cells and red blood cells (cell count), albumin level, gram stain and culture for any possible organisms, amylase level, glucose, total protein, and cytology (malignant or cancerous cells) are analyzed in the laboratory. The results are then analyzed by the treating doctor for further evaluation and determination of the possible cause of ascites.

What is the treatment for ascites?

The treatment of ascites largely depends on the underlying cause. For example, peritoneal carcinomatosis or malignant ascites may be treated by surgical resection of the cancer and chemotherapy, while management of ascites related to heart failure is directed toward treating heart failure with medical management and dietary restrictions.

Because cirrhosis of the liver is the main cause of ascites, it will be the main focus of this section.

Diet

Managing ascites in patients with cirrhosis typically involves limiting dietary sodium intake and the use of diuretics (water pills). Restricting dietary sodium (salt) intake to less than 2 grams per day is very practical, successful, and widely recommended for patients with ascites. In majority of cases, this approach needs to be combined with the use of diuretics as salt restriction alone is generally not an effective way to treat ascites. Consultation with a nutrition expert in regards to daily salt restriction can be very helpful for patients with ascites.

Medication

Diuretics increase water and salt excretion from the kidneys. The recommended diuretic regimen in the setting of liver related ascites is a combination of spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix). Single daily dose of 100 milligrams of spironolactone and 40 milligrams of furosemide is the usual recommended initial dosage. This can be gradually increased to obtain appropriate response to the maximum dosage of 400 milligrams of spironolactone and 160 milligrams of furosemide, as long as the patient can tolerate the dose increase without any side effects. Taking these medications together in the morning is typically advised to prevent frequent urination during the night.

Therapeutic paracentesis

For patients who do not respond well to or cannot tolerate the above regimen, frequent therapeutic paracentesis (a needle carefully is placed into the abdominal area, under sterile conditions) can be performed to remove large amounts of fluids. A few liters (up to 4 to 5 liters) of fluid can be removed safely by this procedure each time. For patients with malignant ascites, this procedure may also be more effective than diuretic use.

Surgery

For more refractory cases, surgical procedures may be necessary to control the ascites. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) is procedure done through the internal jugular vein (the main vein in the neck) under local anesthesia by an interventional radiologist. A shunt is placed between the portal venous system and the systemic venous system (veins returning blood back to the heart), thereby reducing the portal pressure. This procedure is reserved for patients who have minimal response to aggressive medical treatment. It has been shown to reduce ascites and either limit or eliminate the use of diuretics in a majority of cases performed. However, it is associated with significant complications such as hepatic encephalopathy (confusion) and even death.

More traditional shunt placements (peritoneovenous shunt and systemic portosystemic shunt) have been essentially abandoned due to their high rate of complications.

Liver transplant

Finally, liver transplantation for advanced cirrhosis may be considered a treatment for ascites due to liver failure. Liver transplant involves a very complicated and prolonged process and it requires very close monitoring and management by transplant specialists.

What are the complications for ascites?

Some complications of ascites can be related to its size. The accumulation of fluid may cause breathing difficulties by compressing the diaphragm and formation of pleural effusion.

Infections are another serious complication of ascites. In patients with ascites related to portal hypertension, bacteria from the gut may spontaneously invade the peritoneal fluid (ascites) and cause an infection. This is called spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or SBP. Antibodies are rare in ascites and, therefore, the immune response in the ascitic fluid is very limited. The diagnosis of SBP is made by performing a paracentesis and analyzing the fluid for the number of white blood cells or evidence of bacterial growth.

Hepatorenal syndrome is a rare, but serious and potentially deadly (average survival rates range from 2 weeks to about 3 months) complication of ascites related to cirrhosis of the liver leading to progressive kidney failure. The exact mechanism of this syndrome is not well known, but it may result from shifts in fluids, impaired blood flow to the kidneys, overuse of diuretics, and administration of contrasts or drugs that may be harmful to the kidney.

Can ascites be prevented?

The prevention of ascites largely involves preventing the risk factors of the underlying conditions leading to ascites.

In patients with known advanced liver disease and cirrhosis of any cause, avoidance of alcohol intake can markedly reduce the risk of forming ascites. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, etc.)] should also be limited in patients with cirrhosis as they may diminish the blood flow to the kidneys, thus, limiting the salt and water excretion. Complying with dietary salt restrictions is also another simple preventive measure to reduce ascites.

What is the outlook (prognosis) for ascites?

The outlook on ascites primarily depends on its underlying cause and severity.

In general, the prognosis of malignant ascites is poor. Most cases have a mean survival time between 20 to 58 weeks, depending on the type of malignancy as shown by a group of investigators.

Ascites due to cirrhosis usually is a sign of advanced liver disease and it usually has a fair prognosis (3 year survival about 50%).

Ascites due to heart failure has a fair prognosis as the patient may live years with appropriate treatments (survival averaged about 1.7 years for men and about 3.8 for women in one large study).

Ascites At A Glance

- Ascites refers to abnormal accumulation fluid in the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity.

- The most common cause of ascites is cirrhosis of the liver.

- Treatment of ascites depends on its underlying cause.

Other sources of information on ascites

- eMedicine.com, "Ascites."

- eMedicineHealth.com, "Congestive Heart Failure."

- eMedicine.com, "Cardiac Cirrhosis."

sourceLast Editorial Review: 7/13/2009

|

Bookmark this post:

|

|

0 comments

Post a Comment